The Fulbright program shaped some of my earliest childhood memories. In 1967, my father received a Fulbright to National Tsing Hua University in Hsinchu, Taiwan. A math professor at Penn State University in State College, Pennsylvania, he and my mother had never been to another country (except perhaps a trip across Niagara Falls to the Canadian side of the border). They packed up their five children, ranging in age from 2- to 8-years old and traveled to Taiwan. As a 4 year-old, I attended a local Mandarin-speaking pre-school and spent much of my time riding my tricycle, playing with my siblings and little friends, as well as exploring the environs of our neighborhood. Snippets of our year and the many adventures we had reside in my memory, perhaps shaped by the hundreds of slides that my father took during our year abroad, but nevertheless an important source of family stories and identity. From an early age, I understood the joy and wonder of immersion in another culture.

Taiwan remained connected to my family. For many years, a globe sat in our home with my father’s faded pen marks tracing our route to Taiwan and a subsequent round-the-world trip that we took at the end of our Fulbright year. As well, there were the beautiful quípáo that my mother brought back and wore on special occasions, such as our annual visit to a Chinese lunar new year party in State College. And, there was our beloved dining room table, a huge round, hand-carved piece with its center rotating tray, made in Taiwan and shipped to our home. It continues to be the table we gather around for family meals. Finally, there were the Taiwanese friends with whom my parents stayed in touch and the many Taiwanese graduate students that my father welcomed to Penn State over the years.

My parents loved the Chinese tradition of eating at round tables and bought a hand-carved wooden dining table in Taiwan, which was then shipped to the United States in 1968. It has remained as our family dinner table ever since. For me, these tables represent community and egalitarianism.

Consequently, returning to Taiwan over 50 years later with my teenage daughter on a Fulbright to teach American history felt like the completion of some cosmic circle. Similarly, learning that my host, National Taiwan University (NTU), resided on Roosevelt Road, a name shared with my home institution (Roosevelt University) made me feel even more connected to this beautiful island in the Pacific Ocean.

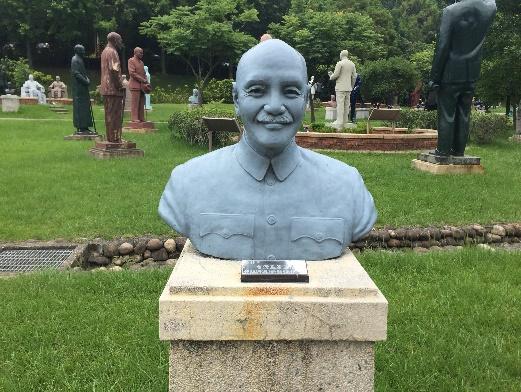

That link, however, was filtered through the eyes of a 4-year-old along with family stories and photos associated with our year in Taiwan. In other words, my images of Taiwan had largely been shaped by personal memory, not researched history. My parents recalled the Fulbright reception they attended, where they shook hands with Chiang Kai-shek and I heard my parents speak of their Taiwan friends who were eager to emigrate to the United States. As a child, it did not occur to me that Chiang’s regime was authoritarian and it was not until I was a young adult that I realized that Taiwan had been under martial law while we were there. One of the first places I visited when I arrived for my Fulbright semester (after I had finished my quarantine) was the 228 Peace Park with its memorial to this 1947 event (see photo right). Guide books and other sources spoke of the protests against government restrictions after World War Two when Taiwan became part of China once again. They also described the subsequent brutal crackdown in which government officials killed up to 28,000 people. Here I confronted the distance between memory and history.

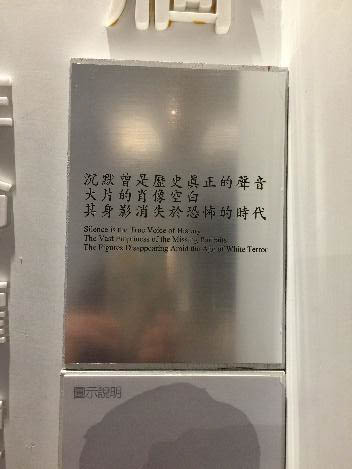

In searching for additional information for the martial law period, now referred to as the era of “White Terror,” I learned the story of Professor Chen Wen-chen (see below) and the dedication of a memorial to him on the campus of National Taiwan University, where I was teaching. When I looked at the date of the dedication, I was startled. It had been in early February, just a few weeks after my arrival in Taiwan. Realizing that his parents had been requesting this memorial for years, I began to understand the complex and far reaching legacy of the rule of Chiang and his son.

Left and center, images of victims of the 2-28 Incident from the museum dedicated to the event. Right, the Chen Wen-chen memorial at NTU, dedicated February 2021. Professor Chen was an NTU graduate, democracy advocate and math professor at Carnegie-Mellon. He was killed in 1981 during a visit to Taiwan and his body discovered on this spot. It is almost certain that he was killed by Taiwan’s security forces.

When I began teaching American history at NTU, Taiwan’s history naturally came up. In a conversation about the 2-28 incident before class one day, a student shared that her great uncle had been one of the victims and that the family had for years visited his grave frequently. She said that her family, particularly her grandfather (brother of the victim) had been deeply affected by this trauma. Reading a book on Taiwan history by one of my NTU colleagues, Chou Wan-yao (gifted to me by NTU Professor Yang Su-hsien, who had helped arrange my visit) gave me additional insight into how challenging it was for people to navigate through the period of martial law. While casual reading of newspaper articles had led me to believe that Taiwan had transitioned relatively peacefully from authoritarianism to democracy, I now realized that this movement was difficult and painful.

My students made me feel connected to a new Taiwan, populated by a generation who has not experienced the martial law era personally because they grew up under democracy. Even so, as the story of my student with the relative killed in 1947 revealed, they live with the legacy of Taiwan’s authoritarianism. Whenever possible, I encouraged them to think about the fragility of democracy and the need for a constant reinforcement of its ideals. In two classes—one on the U.S. in the late 19th/early 20th century and the other on the era of the Great Depression–we discussed ideas, events, groups, social movements and individuals as we sought to piece together American’s own fraught relationship of democracy to capitalism and community to individualism.

Rather than use a textbook, I relied heavily on primary sources in an effort to put students in conversation with voices of the past. For instance, we read an 1887 novel by Edward Bellamy, Looking Backward, that addressed tensions between individualism and community. The novel gave them a strong sense of the class conflict in late 19th century American society along with the utopian visions expressed by idealistic Americans. (Interestingly, this influential novel was translated into Chinese in the late 19th/early 20th century, suggesting its global reach.) Students responded positively to this type of hands-on learning with sources and commented positively about the wide variety of material I used in class, such as artwork, documentaries, Hollywood movies, photographs and artifacts.

In my class on the Great Depression and New Deal, students read letters from ordinary Americans to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt that opened up class dialogue about the emotions and politics of people who experienced poverty and racism in this era. We compared questions of class, ethnicity and social welfare in Taiwan to the U.S. and spoke about President Roosevelt, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and their policies and philosophies of governance. While I had not intended to take the class into the history of World War Two, I realized that there was a strong interest in the topic, so I rearranged the syllabus so that we could spend our last few weeks of the semester discussing it. Again, their experiences and knowledge helped reframe my understanding of the war in the United States. Throughout the semester, I felt the mission of the Fulbright program – exchange and mutual understanding – at the heart of the connections I made to my students.

My Fulbright semester in Taiwan was relatively brief, and somewhat circumscribed by the Covid-19 pandemic, which necessitated quarantine at the beginning and level 3 restrictions at the end. Nevertheless, I managed to connect to communities: to my fellow Fulbrighters, especially during a wonderful conference weekend in Penghu (a true highlight of the semester); to my colleagues and students at NTU; and to others I met through these networks, such as my dear friend Jolene who took me sightseeing and then shared home cooked meals with me throughout the level 3 Covid-19 restrictions. I gave a total of 7 special lectures and presentations, most of which included convivial dinners afterward. These communities helped me forge new memories of Taiwan, now more informed and enlightened by a study of its history. These memories and this history will find their way into my American history classes at Roosevelt University, while the connections and communities I have created will continue to enrich my life, just as they have for my parents. Gratitude, Fulbright!

Managing Editor: 陳韋名 Wei-Ming Chen