As a Fulbright China Transfer due to the unfortunately regressive administrative decision that suspended Fulbright program for mainland China and Hong Kong in 2020, I was very grateful to be offered an opportunity to change the destination of my field research to an alternative location. I chose Taiwan, a place I had always wanted to visit, and perceived this to be an important step for me to carry out my long-term goal for comparative studies in socially engaged public art from East Asia, starting with Greater China, which includes mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. In the past, my primary research area was mainland China and I also had the opportunity to conduct brief field research in Hong Kong and Macau. Taiwan was the only part of Greater China that I had never visited. While I had read a number of publications on socially engaged public art and art-led social activism from Taiwan and have collaborated with a number of Taiwanese scholars through conference presentations and publications, I had no first-hand exposure of the physical, spatial, and sociocultural conditions within which Taiwan artists and art collectives have been working. A six-month research time in Taiwan, I thought, would be invaluable to gain a greater understanding of the specific social, cultural, and political contexts that socially engaged public art has evolved and thrived since the 1990s.

My impression of Taipei

With all these thoughts in mind, I embarked on my journey to Taiwan and arrived on February 1, 2021. After completing the required quarantine period in Taipei, I began exploring the city. I visited art museums and art districts and walked around its historic and new neighborhoods. I was immediately astonished by the vibrancy and diversity of urban life in the city, as well as the number of people on the street, for which I thought being isolated in quarantine for two weeks and before that more than a half-year of work-from-home in the US played a role. Furthermore, the urban fabric of Taipei is very rich and small-business friendly, especially in alleyways where there are a variety of small shops selling inexpensive food and merchandise. One could find magnificent skyscrapers next to rundown old houses, western-style shopping malls and traditional family-run shops in close proximity, and broad and clean main streets punctuated by cluttered and sometimes unkempt alleyways. I loved walking into these alleyways and checked out very small family-run shops, many claiming to be two or three generations. Many of these shops are old, spartanly furnished, and certainly not clean. The fact that there is no separation between retail spaces and residential spaces, shops opening on the first floor with second floor up serving as living quarters, is a valuable trait of the city.

Unfortunately, waves of urbanization have wiped out these kinds of shops and together with it’s the rich historical urban fabric in most cities in mainland China, as new codes of regulating urban spaces were introduced that artificially separate commercial areas from living areas, often out of the concern not for the livelihood of people but the convenience of top-down management, that have effectively taken away all the energy and vitality born out of people’s daily need. While to the eye of a modernist urban planner, the mixing of commercial areas and living areas presents chaos, it actually keeps the cost for living and doing business down and provides tremendous convenience for people living in the area, especially the lower class. This might explain why there are very few homeless people on the street in Taipei, a striking difference in comparison with Los Angeles, the city I came from where social inequality is apparent in its urban planning and management. Given that Taipei is the capital city of Taiwan, I imagined other cities in Taiwan would bear this trait in terms of urban planning and was confirmed later when I visited other cities.

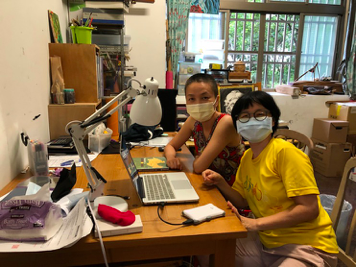

My field research (please see a few photos below)

Taipei Biennial

My field research officially started when professor Weihsiu Tung, my host from National University of Tainan, came up to Taipei to meet me in late February and together we visited the ongoing Taipei Biennial at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum. The theme of this round of Taipei Biennial, “You and I Don’t Live on the Same Planet,” happened to be so relevant to our torn human world where people are impacted so differently by the climate change, the pandemic, and the economic downturn that they might as well consider themselves living in different planets with different destinies. It is an honest portrayal of our divided world and a timely warning.

The Bamboo Curtain Studio

The Bamboo Curtain Studio was one of the important art spaces from Taiwan that I have heard about long ago and I was very happy to pay a visit in late February and then a second visit in March. Founded in 1995, the Bamboo Curtain Studio in Tamsui District, New Taipei City, has been a very important grassroots organization and likely the first one to promote cross-cultural exchanges for art professionals from across the globe. It has hosted numerous artists working in national and international art related fields via residency programs and has sponsored or initiated important exhibitions, performances, and community-based art and cultural events. For example, the well-known and much discussed “Art as Environment: A Cultural Action at the Plum Tree Creek” project was launched by Bamboo Curtain Studio in 2009 in collaboration with Wu Mali, a Taiwan artist and curator known for her community engaged public art projects. The project employed art as an intervention to stimulate collaboration among professionals, the Zhu-Wei neighborhood residents, and the public sectors in order to raise public awareness about pollution and water flow issues of the area’s Plum Tree Creek and facilitate the of reclaim of the ownership over their natural resources.

Unfortunately, this pioneering art space had to shut down this year, after about 25 years’ operation as an incubator for new ideas and practice of contemporary art, especially socially engaged art. The closure appeared to be due to two main reasons. For one, the landlord decided not to continue leasing out the property to the art space; second, the founder teacher Xiao was in her advanced age and was not able to keep up with the operation of the space. Nonetheless, I felt fortunate enough to be able to visit before its closure and also able to attend its two-day online forums as a summary of this organization in early July.

The Yellow Butterfly Festival

Meinung town, the location for the Yellow Butterfly Festival, was another important destination of my field research and I was able to visit it multiple times starting in March, sometimes staying a week or more to meet and interview chief organizers, artists, and participants as well as to attend some activities. Yellow Butterfly Festival is a community-based annual festival launched also in 1995 by two grassroots organizations in partnership with the local members in Meinung, a beautiful rural town of Hakka population known for its history of agrarian lifestyle as well as its rich Hakka traditional culture and customs. A by-product of the famous social movement, the Meinung Anti-dam campaign, this festival originated from concerns of ecological degradation and still focuses on environmental protection, ecological consciousness, and sustainable development. Overtime, it has fostered a vibrant local community culture centering on environmentally-friendly agricultural production, sustainable lifestyle experiment, and public art development, among others. In recent years, it has taken upon the identity of an environmental art festival that is locally based with a global vision and has adopted the format of an art biennial starting in 2015 with various preparatory activities starting several months before its core programs, which usually take place in July.

This year, this 27 years old festival faces the challenge of the pandemic and has to cancel most of its outdoor activities since mid-May that used to attract a huge number of active participants and the general public. Nonetheless, the organizers have adjusted their programs for online delivery and allowed me to do online participatory observation.

Traveling Around

After settling in Tainan, I began travelling extensively to attend public events related with art in Chiayi, Kaohsiung, Pingtung, Hualien, locally in Tainan, and of course Taipei now and then. I also visited art museums, galleries, cultural and educational foundations, art collectives, as well as individual artists and art professionals who were willing to meet me and show me around their studios or neighborhoods. Major public art festivals that I was able to visit, before the sudden outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic that shut down the entire island, included Chiayi International Art Doc Film Festival in Chiayi, Longci Light Festival in Tainan, Luoshanfeng Arts Festival in Pingtung county, and Yuguang Island Art Festival. Besides, I also visited the headquarter of several NGOs such as Hsin Kang Foundation of Culture and Education (founded in 1987)in Chiayi county, Zhong Lihe Foundation of Culture and Education (founded in 1989) in Kaohsiung city, and Louyoung Cultural and Educational Foundation (founded in 1995) in Yunlin county and learnt about their work in community building and local cultural development. I was extremely impressed by the foresights of these community leaders and their perseverance in grassroots mobilization via art and cultural activities.

The end, for now

Six months seem to have flown by too quickly and I can easily see myself spending another six months learning about all exciting and inspiring community-engaged public art and cultural endeavors that are not only grounded in the specific socioeconomic and political conditions of Taiwan but also speak to some fundamental human needs no matter where one lives: clean water, clear air, safe and vibrant community, meaningful work and life, and fulfilling relationship with fellow human beings and nature. I surely cannot wait to write up my findings and seek opportunities to share with others.

Research photos

Managing Editor: 陳韋名 Wei-Ming Chen