Taiwanese folk religion, or Taiwanese Taoism, worships hundreds of gods. Most of these gods were imported from China, and if you look at their histories, you will find that long, long ago, the majority were once real people, who were said to have accomplished feats of great heroism or compassion during their time alive. As time progresses, histories become folklore, and the dead become gods. Taiwan, where Taiwanese folk religion has only existed for roughly four centuries, has very few of its “own” gods. Arguably, many of the gods that originally came over from China now belong to Taiwan as much as, or in some cases even more than they belong to China, but what about gods whose origin stories are on Taiwanese soil? Beginning in 2023, I set out to study and collect these narratives, and document the associated locations with my large format camera. Following this field work, I gathered a crew and shot a film, which I will briefly elaborate on after I share the central concepts and stories of my project.

In 2021, I visited a friend in Taichung, where we went to the Taichung National Museum of Fine Arts. There I saw Yihao Yu Gou 一號與狗 [Number One and the Dog], a five minute experimental film by artist Wu Chi-Yu addressing some of the stories and geography surrounding the Temple of the Eighteen Lords (十八王公廟). After seeing the film,I was intrigued by the godhood of the dog, so I decided to visit the temple myself. There I learned the origin story of the Eighteen Lords: in the mid 1800s, a ship carrying seventeen people and one dog, likely men immigrating from China, experienced a shipwreck just off the northernmost coast of Taiwan. The men died in the wreck, but the dog was able to bring all the bodies to shore before passing away himself. At first, there was no temple, but only a mass grave on the shore. Over time, locals who prayed there found the Eighteen Lords to be efficacious, and the grave was modified to be a small temple, and then a larger one. Since not much time has passed, the memory of the shipwreck and the fact that the Eighteen Lords were once mere mortals lingers. The Eighteen Lords are often viewed as high-level ghosts or low-level gods, and thus the temple is considered an yin 陰 temple, as opposed to the majority of temples which are considered yang 陽. Like other gods of yin temples, the Eighteen Lords are primarily worshiped at night, although the temple is open during daytime hours as well. Conversely, yang temples are only open during the day. During my first few visits there, I too found the Eighteen Lords to be particularly efficacious, and made fast friends with the night shift temple keeper. I have continued to make midnight visits at least once a month ever since.

That experience inspired me to look further, and I discovered that many of the gods truly local to Taiwan were considered yin, as their deaths were more recent (i.e. within the past four hundred years), and often tragic. The establishment of these gods was in response to tragedy or to prevent further calamity and other bad luck. The gods at yin temples are primarily worshiped at night, often have their remains housed in the temple, and are burdened with task of responding to all prayers regardless of what the worshiper’s requests are (有求必應). I expect that after several hundred more years, it is likely that some of these gods will have come to be considered yang, as history, memory, and lore are entangled by the passing of time. Yet another type of yin temple is typically given names such as Youying Gong Temple (有應公廟) or Wanshan Gong Temple (萬善公廟). These are usually very small temples placed to placate ghosts of unattended graveyards or unidentified remains that were inadvertently dug up during construction projects. These ghosts have less specific history and identity, which makes them truly just ghosts, and their status is unlikely to be elevated in the future. Although this practice is very interesting, this type of temple is not the focus of my discussion and project.

Prior to my first yin temple encounter when I visited the Eighteen Lords, I had already been a part of the religious community for some time; I was buddhist-leaning as a child in Taiwan, and as an adult made the move toward folk religion and began performing in ritual temple events. Despite my involvement in the Taoist community, I was not aware that there were temples housing gods considered to be “ghosts”, beings of the spirit realm, or however else they might be described, nor was I aware of the differences in histories and taboos associated with them. Even people who are deeply involved in the temple community often know very little about yin temples; they only tell others to stay away from yin temples due to the fear of ghosts. While the temple of the Eighteen Lords is the most famous temple considered an yin temple in Taiwan, there are many others.

Here I will share some of their stories:

Wai’ao Jindou Gong Temple (外澳金斗公廟), Yilan

A few hundred years ago in front of the current temple location, bones were scooped up from the ocean in a fisherman’s net. At first, they were placed in an urn on the shore, where local fishermen would pay their respects, and sometimes pray. As prayers were answered, they decided to move the urn and build a temple for the bones. While they were moving it, the urn somehow became wedged between two boulders, so that’s where it stayed—and they built the temple over the urn and around the rocks. A house is attached to the side of the temple, and in the house lives a family who has taken care of the temple for generations. While the temple was built roughly 200 years ago, there was a long period of time when there was just a small shrine, and even a period of time when there was just an urn sitting on the rocks—even the caretaker is unsure of how long ago the bones were first found.

Laoda Gong Temple (老大公廟), Jilong

In the 1800s, Quanzhou and Zhangzhou people had settled in and around the small port city of Jilong. The two groups fought constantly over the land. In 1851, a large battle broke out between them, and well over 100 people died, which was a large percentage of the settlers. Many bodies of both parties were thrown into the Nanrong river, and were not retrieved until days later. By that time, they’d been eaten by fish to the point of being unrecognizable, and some fish were even found trapped swimming inside their skulls. The dead were collected, and as it became popular to pray to their graves and ashes for various requests, a temple (老大公廟) was eventually built to house these unidentified dead, who have since been promoted to near-god status through efficacy and popularity.

Sansheng Shuigui Gong Temple (三聖水櫃公廟), Miaoli

In Southern Miaoli, it is said that a water tank floated to shore and was discovered by fishermen. When they opened it, they discovered that it had been nailed shut from the inside, and there were three bodies inside. The fishermen buried the water tank, and the site was initially set up as a tomb. Local fishermen increasingly worshiped the grave, and in the early to mid 1900s a temple was built at the site. Again, we cannot estimate the date of the origin story by when the temple was built, because ghosts often take some time to prove themselves worthy of a temple.

Caotun Nan’an Seven Generals Temple (草屯南岸七將軍廟), Nantou

In the late Qing dynasty (1644-1911), it is said that while 6 workers, accompanied by their dog, were working on digging a pathway for a flood control system in Nantou, they were suddenly swept away by uncontrolled waters. Part of what remains of the flood control system is still there, if you are willing to dig up an old man’s compost heap and potted plants. Unlike the other temples, no physical remains were left to be placed in the temple. The dog god here, seems to have more of a pet appeal than the dog at the Temple of the Eighteen Lords. While I was there, I met a family who had traveled down from Taipei to repay the dog god for answering their prayers to heal their family dog. They told me they initially came down to pray when they saw the god had healed other dogs on the news.

Shuiliu Ma Temple (水流媽廟), Jiayi

In rural Minxiong of Jiayi county, a temple worships a skull that was once found clogging the stream by the rice fields. The skull was fished out and placed in an urn next to the stream, where people would pay their respects. At the time, there was only a narrow bridge of bamboo tied together with which to cross the stream, and as a little boy crossed the bridge one day, he fell into the stream. The boy explained later that as he fell, a woman used a prickly bamboo plant to catch him by the collar and pull him back up, and he knew the woman to be Shuiliu Ma, the owner of the skull. This is likely the first tale of Shuiliu Ma’s deeds. Following this the urn was frequently worshiped, and later a temple was built.

Tiegu Shan Temple & Coffin Cave (鐵谷山宮, 棺材窟), Tainan

Roughly 100 years ago, around the time of the Xilai Temple anti-Japanese uprising, an anti-Japanese rebel by the name of Fang Dazhuang operated from the mountains of rural Tainan. It is said that he killed a number of Japanese soldiers in a place which English texts call “Coffin Cave”. After he was captured and killed, a temple was built not far from Coffin Cave to worship him and three other anti-Japanese heroes. We set off into a rural mountainous area with no reception thinking that we were looking for a cave. As we neared the temple, called Tiegu Shan Temple, we began to stop and ask for leads on Coffin Cave at each of the few residences and shops we passed. No one knew what we were talking about. There was no one at the temple either. Eventually, someone sent us back to ask a different temple down the road, who gave us vague directions to drive up a narrow dirt mountain road until it ended, and then get out and river trace until we found two water pits. They weren’t caves after all, they were water pits which the bodies had become trapped in as they floated downstream.

Sometimes calamity leads to the construction of a temple, but then, instead of worshiping those lost in the calamity, an orthodox (zheng or yang) god that is able to suppress or control the yin traces left behind by the tragic events is installed at the location.

Longtian Yisheng Temple (隆田義聖宮), Tainan

In Tainan, on March 11th 1961, a vehicle carrying soldiers from the nearby training center was crossing the train tracks. When they saw the train, it was too late. Over 20 soldiers died. Following the event, the homes and shops in the vicinity of the accident began to report seeing and hearing strange things, finding silver ghost money in their tills, and an increase in accidents at a nearby intersection. Rather than paying respects to the ghosts, someone put the god Li Er (李二王元帥) in a small makeshift shrine near the site of the accident to appease the ghosts. Eventually, as this proved effective, a larger temple for Li Erwas built to keep the area at peace.

Dajia River God 大甲溪河神廟, Taichung

In the mid-1900s, the Dajia area suffered from frequent flooding. A farmer dreamed of an old man standing at the edge of the river and driving the floodwaters back into it. When he went to work in the fields the next morning, he looked in the tributary which watered his crops and found a large head-shaped rock with a face similar to the man in his dream. He pulled the rock from the water, and people began to worship the rock as the river god at the Dajia River God Temple.

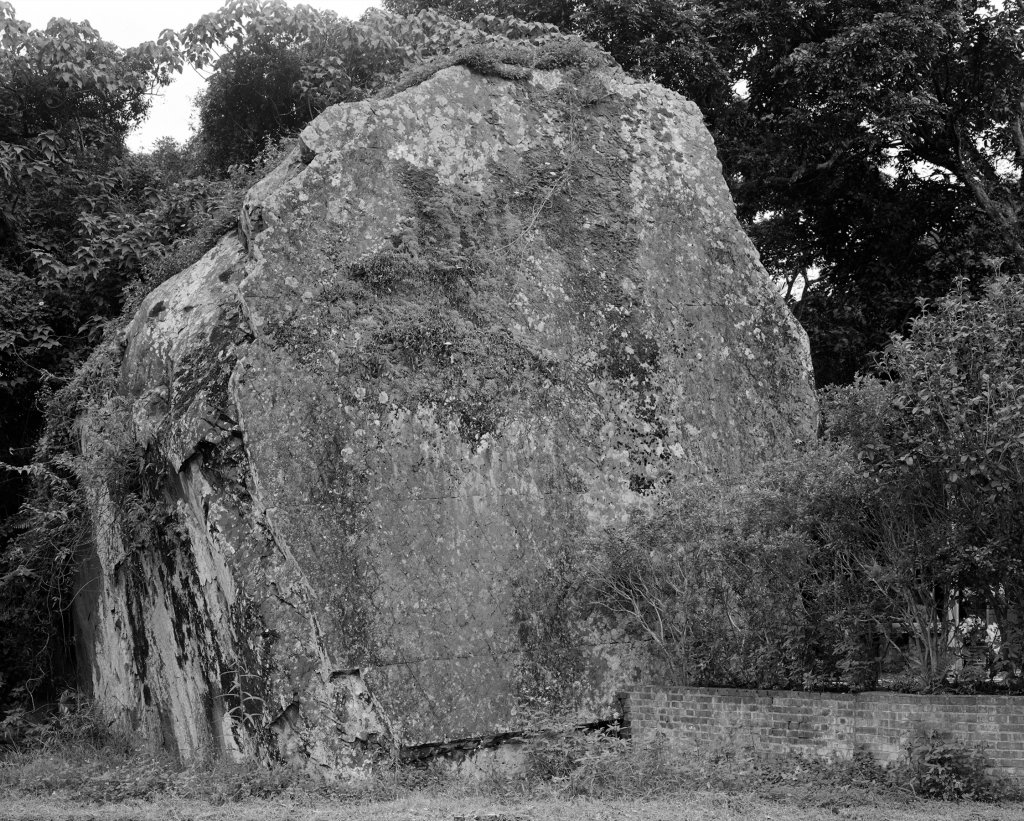

Shijing Tai (石鏡台), Yilan

This rock is called Shijingtai. I initially discovered the large boulder named Shijingtai as I was researching a different story in Yilan—a story in which a cat demon devastated local farms and homes regularly, until it was captured, reasoned with, and became worshiped as a god (貓將軍). Shijingtai aided in the capture of the demon, and I found it to be more interesting than the story of the cat demon itself. Shijing Tai has a flat face, which is tilted up, facing into the mountains ahead of it. It is said that it exposes all evil, or the true nature of all things, which crosses into its path.

Tragedies dealt with by the Taoist folk religion community don’t always lead to the establishment of a temple. Sometimes they are addressed only through ritual, and leave a lasting trace at the location and memory in the community.

Song Rouzong (送肉粽), Zhanghua

This ritual is generally only used in the city of Lugang in Zhanghua county, and the circumstances that must occur to require this ritual are fortunately rare, so it only happens once every few years. The last time this ritual was performed was 4 years ago—to expel the resentment attached to the site and implements of a suicide by hanging. During this ritual, any remaining physical evidence of the tragic event is transported on foot to be burned at the ocean shore, no matter how far that may be. Before the rope is taken through the streets to be burned at the ocean shore, every wall, tree, door, and window on the predetermined route is plastered with protective talismans. In the hours leading up to the excursion, stores have closed early and everyone has gone home. Visual documentation of the ritual itself is prohibited.

2007 Tree Incident (殺人的樹, 2007事件), Jiayi

In 2007, tragedy began in a small village in Southern Jiayi. Villagers died at an alarming rate that year—especially alarming considering that in a town of less than 300 people, it’s quite a big deal for even one person to die in a year. That year, a total of 16 people died. They asked the god at the local temple for answers, and discovered that the deaths were linked to the death of a several hundred year old tree in the village, which had died around the time the first villager passed. Every villager, with no exceptions, made a straw substitute of themselves, and then the straw people were burned. After that, the deaths stopped. Curiously, the tree

sprouted new growth a few years later.

What I have written here is but a brief overview of the concept of yin temples in relation to historical events and in contrast to yang temples, and short summaries of a few stories. I share these stories and my thoughts on them in hopes that people may seek to understand them better and not fear them, and it is my hope that this record will prevent the stories from dying out.

My initial study of such locations and their stories was conducted through five months of field work, which included photographing locations with my traditional analog large format camera and recording interviews and other conversations. Following this period of field work, I spent 5 months shooting and editing a 47 minute experimental film Gathering Dirt, Burning Incense, (撮土焚香). In a surrealist narrative framework, I explore the origin stories of yin temples (陰廟) and other happenings in the local taiwanese taoist community, as well as the concept of locational power & memory. This film will go on to screen at film festivals internationally, and I am also preparing a book that will include photographs, stories, and interviews. I am left with a substantial archive of raw video footage and other material with which I expect to make additional work, along with many more interesting leads to follow in Taiwan.