My classmates and I took an unorthodox route to Keelung. Instead of riding a bus, we took the old coal mine railway that passed by the Ching-Tung Coal Mine Museum. Once we arrived at the train station, the dark clouds overhead let loose torrential rain that demonstrated why locals call Keelung the “rainy city.” This detour was arranged by our program director so that we could have an opportunity to learn about local history before heading to National Taiwan Ocean University (NTOU) for a joint workshop on ocean development and revitalization. I was excited to represent my school, National Chengchi University (NCCU), by presenting my research on European maritime power in the Pacific during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. However, my interest in Keelung began during a Taiwanese history class I took this semester.

Since the early twentieth century, Keelung was a site of intensive development by Japanese colonial authorities, who sought to improve Taiwan’s northernmost port due to its proximity to Japan. The intense colonial attention given to the city included a shifting array of assimilation policies. The Taiwanese response to these policies was the focus of Becoming Taiwanese by Evan Dawley. Dawley’s research uses the “crucible of Keelung”— or Kiirun, as it was called during Japanese colonization (1895-1945)—as a microcosm to demonstrate how Japanese policies enacted throughout Taiwan gave its inhabitants a shared experience that later became a foundation for Taiwanese identity.

An important feature of Japanese colonial policies were their implicit contradictions. In Keelung, the Japanese created social welfare organizations, mandated the study of Japanese, development industry, and funded the construction of Shinto shrines. However, these policies also proved alienating. Japanese became the language of educated Taiwanese and many studied in Japan, but almost all were forced to return to home. The Taiwanese were allowed to form elected councils as part of the Japanese experiment with Taishō era democracy, but local decisions could contradict edicts from the mainland. Moreover, the Taiwanese lacked meaningful representation in the national legislature.

Even the residences of Keelung, which were divided into Japanese and Taiwanese sections, evinced Japanese ambivalence towards full assimilation. Religiously, Shinto emphasized a shared divine heritage of the ethnic Japanese, drawing a distinct line between colonizer and colonized. Therefore, Japanese colonization exposed the Taiwanese to colonial modernity without affording them the full rights enjoyed by the Japanese. When applied to the whole island, these unequal policies created a shared experience of inequality that differentiated the Taiwanese from the Japanese and contradicted the liberal elements of Taishō thought during the 1920s.

My historical study of colonial Keelung did not directly relate to the workshop theme, which was ocean development and revitalization. However, colonial history made me think about the relationship between locals and elite, which was a theme that featured prominently in the presentations about revitalization projects. Although Keelung was the site of intense development during Japanese colonization, it received less attention during Republic of China (ROC) rule. However, recent efforts have sought to utilize cultural and environmental tourism to revitalize the city. One area of focus has been the Marine Education and Tourist Park maintained by NTOU.

The concept for this park developed as a creative solution to fulfill the mission of the university and its related museums. While the goals of museums vary by culture and time period, they usually have four principle goals: education, preservation, exhibition, and research production. I first learned about this framework interning at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. However, I learned in this workshop that academics at NTOU have a unique set of challenges. In an art museum, preservation is performed on pieces in the museum collection that can be stored in a carefully controlled environment. Researchers at NTOU, however, face a variety of competing human and environmental factors. The coast was critical for data collection and educational programming, but it was also the site of fishing industry and waste storage. Therefore, NTOU researchers introduced the concept of an ocean park to implement an organized set of policies based on concepts of preservation and education that could coordinate the revitalization of a broad area and protect connected ecosystems. These policies also aimed to attract tourists—a double edged sword in the world of preservation because the site requires revenue but could also be adversely affected by large crowds.

Revitalization and increased tourism did not appeal to everyone; the idea received strong opposition from local fishermen, who feared preservation guidelines would endanger their livelihood. It was a case of highly educated elite coming to an area with priorities and a vision of development that clashed with local interests. This opposition reminded me of a dynamic I encountered in Baltimore, where debates about gentrification are heated and ongoing. Residents of both localities rejected policies that brought capital at the expense of current residents.

NTOU managed to quell most serious opposition to the park using a response that effectively engaged the local community. Through regular talks with the fishermen, organizers were able to understand their needs. Fishermen were integrated into local events as vendors and some have joined the tourism industry by offering experiential expeditions on their boats. Preservationists and fishermen also found mutual ground in initiatives to reduce pollution that was threatening fishery stocks. Through these methods of collaboration, researchers, preservationists, policy makers, and fishermen were able to move their relationship from one of adversarial tension, to mutually beneficial collaboration. However, the researchers with whom I spoke also stressed that finding a balance is an ongoing process, and they continue to engage with the local community.

The creation of a larger park zone also facilitated the development of other neglected areas. For example, the east side of the Badouzi peninsula was being used as a 1000 square meter landfill before the creation of the eco park. After revitalization, the area became Chaojing park, with a clear skyline, modern art instillations, and chairs where visitors can relax. The ecological integrity of the park is overseen by the Chaojing Ocean Research Center, which also functions as a museum: it collects and preserves maritime specimens, conducts educational programs, is a site for original research, and displays marine-related exhibitions. Workshop participants were invited to see the exhibition and research spaces, which are filled with a colorful array of specimens ranging from iridescent tropical fish to brilliant anemone. Our visit also included a peek at the Marine Science Gallery, which featured museum exhibitions. It was interesting to see how the ocean park, which was conceived as an outdoor museum, also featured traditional institutions.

To further increase tourism, planners explored the cultural heritage of the region in addition to the scientific fields that constitute most the university’s preservation endeavors. One example of heritage preservation is the Fishing Village Relics Museum, which sits in a quiet alley in Badouzi port. The museum is filled with model ships, photographs, oil paintings, and old fishing implements. The museum is also affiliated with the publication “Northeast Wind,” which records fishing village culture. The magazine was founded to engage older residents who might be uncomfortable using digital platforms.

It was a real pleasure to learn about how the ocean park brought an innovative approach to museum concepts like education and preservation to create a revitalization project that included scientific discovery, cultural heritage, and was founded on collaboration with local residents. In many senses, this is the type of project that I am interested in learning more about during my Fulbright.

Before I came to Taiwan, my background was primarily focused on history. I had done some work in museum studies that lead me to my aforementioned internship, but the research I conducted was largely focused on the content of history rather than its presentation. It was my goal in coming to NCCU, which has a reputation in the social sciences, to learn more about the intersection between history, academia, and policy. While the specific content of the workshop was primarily concentrated around scientific research, it taught me about how Taiwanese institutions are creating new approaches to preservation and museums—approaches that are self-sufficient and beneficial for local people.

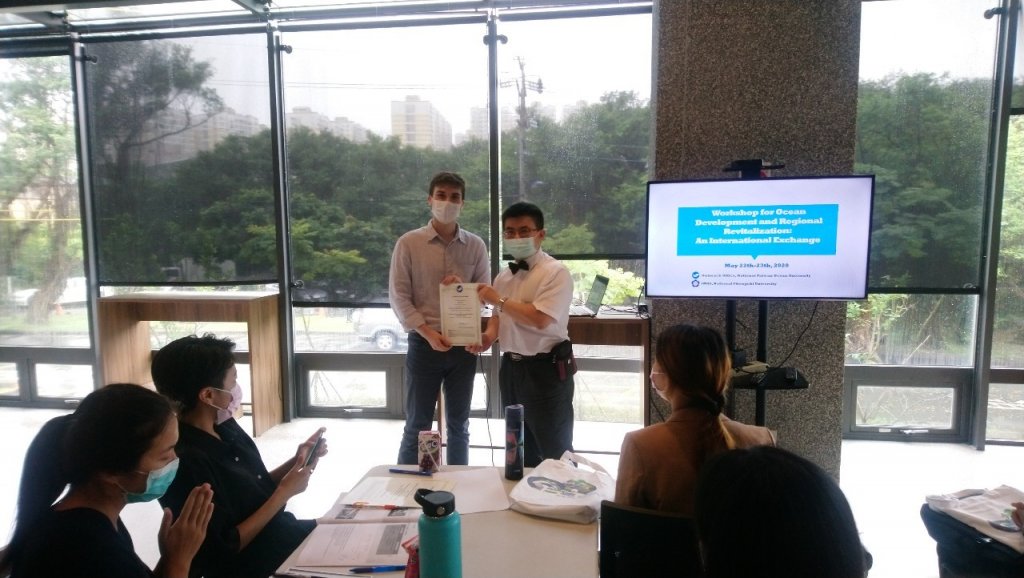

This trip was important to my Fulbright experience for one more reason. Since I arrived in Taiwan, I have enrolled in intensive Chinese classes concurrently with my graduate program. It has been challenging to pursue two fulltime programs simultaneously, but I am determined to improve my Mandarin skills. That is why I wrote my presentation in Chinese when I applied to this workshop. The process of translating my research and then spending hours working with my professors to craft a passably coherent script in academic Chinese was a grueling process, but when my research was accepted, I felt like my hard work was worth it.

For these reasons, my trip to Keelung had important personal resonance for me. It was related to topics I had studied in class, and it was forum where I shared my research using hard-earned language skills, and it gave me an opportunity to explore longstanding interests. However, I do not think one needs this sort of background to appreciate Keelung. From its famous night market to its scenic coast and long history, the rainy city has a lot to offer.